Training load (TL), which combines both the duration and intensity of exercise, is a frequent topic of discussion among coaches and athletes. But what exactly lies behind this key metric that’s so crucial for optimizing training?

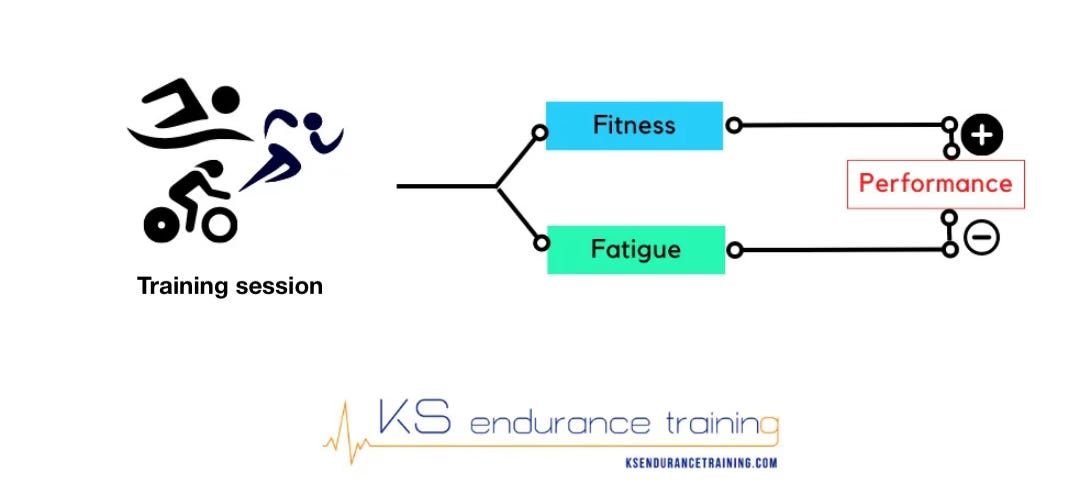

The first studies on training load can be attributed to Banister and his team (1975), who showed that a training session induces stress and fatigue, which can either enhance or diminish performance.

A training session represents a dose of exercise that generates an adaptive response, allowing for an increase in fitness level and improved performance during the recovery period that follows. The magnitude of this fitness improvement depends on the exercise stress: a lower training dose produces less stress, and therefore a weaker adaptive response, compared to a higher dose.

This concept is known as TRIMP (Training Impulse), where each session is considered a "training impulse" that temporarily decreases performance (TDP), with the magnitude of this decrease depending on the training dose.

TRIMP allows us to quantify **internal training load**, using both exercise duration and heart rate (HR).

How to Calculate TRIMP:

- TRIMP = Duration (min) × Intensity (%HRmax) × Weighting Factor

- Intensity = (HRexercise - HRrest) / (HRmax - HRrest)

- Weighting Factor (k) = 0.86 × e^1.67x for women; 0.64 × e^1.92x for men

**Example:**

An athlete with a resting HR of 40 bpm and a max HR of 190 bpm performs a 45-minute exercise with an average heart rate of 160 bpm.

- (160 - 40) / (190 - 40) = 0.8

- 0.86 × e^1.67 × 0.8 = 3.271

- 45 (duration) × 0.8 × 3.271 = 117.756

- So, their training load is **118 TRIMPS**.

Using the TRIMP Load:

Morton and Banister developed the concept of a **limit load** to help prevent overtraining or overreaching, which could harm fitness.

The daily limit load for a regional-level athlete would be 125 TRIMP, while an elite athlete could handle up to 250 TRIMP.

Limitations of the TRIMP Method:

While this method of quantifying training load may look good on paper, it comes with several limitations:

Accurately calculating maximum heart rate (HRmax) can be difficult.

Cumulative training load naturally lowers HR due to various factors affecting the autonomic nervous system (ANS).

Cardiac response can be disrupted by factors such as digestion, stress, fatigue, or temperature.

Cardiac drift during training sessions, typically caused by the buildup of internal heat, can skew results.

Averaging heart rate for an entire session might underestimate the load; a more precise evaluation would involve calculating intensity in different zones during the session.

In swimming sessions, HR cannot be reliably measured for triathletes, making it difficult to track.

These limitations show that this method of quantifying training load is not always the most reliable.

However, Banister and his team made significant progress by quantifying both the negative cumulative effects (fatigue) and the positive cumulative effects (fitness) of training on future performances.

Recap on Training Load:

Monitoring training load is a key aspect of the training process because it helps with:

The daily prescription of training sessions

Adjusting weekly training volume

Preventing injuries, upper respiratory tract infections, or overtraining

Training load represents the total dose of training and the resulting stress placed on the body. It’s a central tool for coaches, who use it to prescribe optimal training based on how the athlete responds, and to predict long-term effects on performance.

Therefore, it's crucial to calculate TL accurately if it's going to be at the heart of the training process.

Most of the scientific work on TL is based on indirect validation, following Banister & al.'s research on the effects of fitness and fatigue on performance. However, as a recent study by Louis Passfield—an expert on the subject who has sadly passed away—pointed out, these concepts were never scientifically validated.